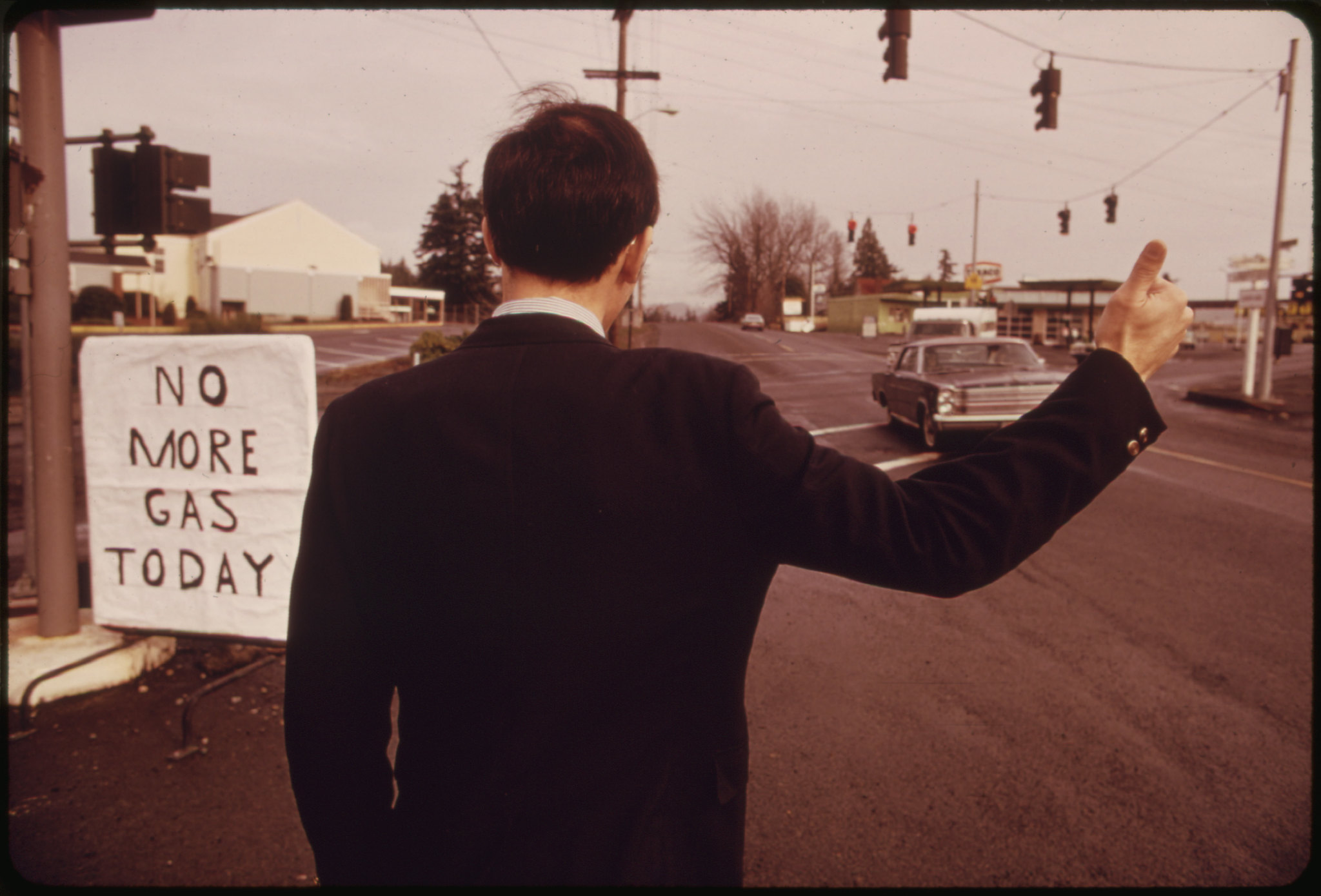

For those with any historical memory, or of a certain age, they may know that the United States once banned exports of crude oil. This started in the mid-1970s, resulting from an oil embargo directed at the United States by selected Middle Eastern countries.

This embargo began after American support for Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. In response, some OPEC nations halted shipments of oil to the United States. The OPEC oil embargo ended in 1974, but the U.S. Congress, fearful of a repeat, banned most U.S. oil exports to preserve oil stocks for domestic use.

It was only in December 2015 that President Barack Obama lifted restrictions on exports of U.S. oil to the rest of the world, effective the following year. The result has been a boom in crude oil exports, rising from 465,000 barrels of oil daily in 2015 to almost 3.2 million barrels per day in 2020.

America’s lifting of its own self-imposed 40-year ban on oil exports is relevant to Canada. For one, it meant the U.S. was now in competition with Canada for oil export customers. It also meant, though, that selected U.S. refineries would need more Canadian heavy oil.

As Oil Sands Magazine has pointed out, this need arose from how increasing American oil production came from U.S. shale plays. This oil has a relatively high API density, a commonly used index for measuring the density of a crude oil or refined products. Crude oil will typically have an API between 15 and 45 degrees. (The higher the API, the lighter the crude, while the lower the API, the heavier the crude.)

The problem for some U.S. refineries is that as the American-sourced domestic supply of crude became increasingly lighter, approaching 40 degrees on the API scale. That created a mismatch with the desired refinery feedstock density, which averages about 32 degrees.

That is where heavier Canadian crude oil (from the oil sands) comes in, as refineries seek to blend light domestic crude with heavy and medium grade oil imports. By adding imported heavy crude oil to domestic light crude oil in the production process, the U.S. has significantly increased its ability to export refined oil.

Declining imports from U.S. heavy oil suppliers in Venezuela and Mexico have also opened the door to more Canadian heavy oil in the Gulf Coast refining cluster, the world’s largest heavy oil processing area.

The result for Canada is that the percentage of total imports of Canadian heavy oil to the U.S. (i.e., with an API Gravity of 25 degrees or less) has risen from 25.1 percent in 2000 to 55.8 percent in 2019. More generally, American imports of oil from Canada have risen from 1.3 million barrels daily in 2000, to two million daily in 2010, and reached 3.8 million barrels daily as of 2019.

This American need for heavy crude oil has been positive for Canada’s oil exports. However, it should be noted that the increased Canadian oil exports to the United States does not mean the various attempts to obstruct Canadian crude oil exploration, production, pipelines and exports have been unsuccessful.

There are multiple examples of the ongoing problem: The Obama administration’s blocking of the Keystone XL pipeline, followed up with a repeat action this January by President Joe Biden during his first day in office, after former president Donald Trump allowed Keystone XL to proceed.

There is also the self-harm in Canada where proposed pipelines such as Northern Gateway and Energy East were thwarted by a combination of politics and activism, i.e., tanker bans on the northern coast of B.C. and anti-oil activism and political opposition in Quebec.

Such killing of alternative markets to the Americans has been costly. That is because a lack of extra pipeline access to coasts means that is has been difficult for Canadian producers to sell oil into non-American markets.

Also, increasing amounts of crude oil are shipped by train instead of pipeline which means such oil is sold at a discount to what it would be if shipped by pipelines.

Before the Coronavirus pandemic temporarily cut into demand, Canadian oil-by-rail shipments to the United States reached nearly 412,000 barrels of oil daily in February 2020, a monthly record. Back in 2012, the earliest year for which data are available, daily crude oil shipments peaked out at only 125,000 (in December) but had been as low as 9,725 barrels of oil daily (in January 2012).

Oil-by-rail is higher risk and more expensive. In 2019, the Fraser Institute estimated that from 2013 to 2017, after accounting for quality differences and transportation costs, the depressed price for Canadian heavy crude oil resulted in C$20.7 billion in foregone revenues for the Canadian energy industry. In 2020, IHS Markit estimated the loss of income for Canadian producers at US$14 billion (between 2015 and 2019 inclusive). IHS called that number “conservative.”

If anyone thinks the United States can do without Canadian oil, including and especially Canadian heavy oil, they are misinformed. Canadian oil is critical to the United States and increasingly, for its own subsequent blended oil for its own oil exports.

Mark Milke and Lennie Kaplan are with the Canadian Energy Centre, an Alberta government corporation funded in part by carbon taxes. They are authors of the report Analyzing the Contributions of the Canadian Crude Oil Sector to U.S. Petroleum Refineries